-

2022

The ESHG Executive Board has officially endorsed the Call to Action from the Expert Conference on Rare Diseases – Towards a new European policy framework on rare diseases: “Building the future together for rare diseases”, October 25 and 26, 2022 in Prague, with special focus on the IVDR-related statements of the document.

The ESHG has addressed a formal letter to the responsible person at the Czech Ministry of Health, the check Republic presiding the Council of the European Union in the second half of 2022, specifically highlighting the importance of lowering the performance study requirements for 'orphan diagnostics' at the beginning of test implementation (when clinically required) without having to lose quality assurance.

- Download Call to Action

- Technical meeting under the auspices of the Presidency of the Czech Republic in the Council of the EU. Brno, Czech Republic, July 23, 2022.

- Download Report: Towards a New European Policy Framework: Building the future together for rare diseases

- Eurordis Press Release: "21 Member States endorse Czech EU Presidency’s Call to Action on rare diseases at EPSCO Council Meeting"

It is 30 years since the first issue of the European Journal of Human genetics was published. To celebrate this, the EJHG publishes a series of comments on significant papers published in the journal in the past 30 years and present an online web collection of papers selected by our editorial board.

Access the online web collection here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41431-022-01188-6

Swedish geneticist Professor Svante Pääbo has won the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discoveries that underpin our understanding of how modern day humans evolved from extinct ancestors. Pääbo, director at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, won the prize for "discoveries concerning the genomes of extinct hominins and human evolution," the Award committee said. “His discoveries provide the basis for exploring what makes us uniquely human.”

Born in Stockholm, Svante Pääbo studied medicine and biochemistry at Uppsala University before creating the scientific discipline paleogenomics, which has shed light on the genetic differences that distinguish living humans from extinct hominins. His ancient forensics work also has implications for modern medicine, for example by showing why some people are at higher risk of severe COVID. In 2020 he and colleagues published a paper showing that a genetic variant inherited by modern humans from Neanderthals when they interbred made those who carried it more likely to require artificial ventilation if infected.

His Nobel comes two years after another ESHG prizewinner, Professor Emmanuelle Charpentier, shared the 2020 Chemistry award with Professor Jennifer Doudna for the invention of the gene-editing technology CRISPR/Cas9. Prof Charpentier gave the ESHG Mendel Lecture at the Society’s annual conference in 2018.

ESHG President, Professor Borut Peterlin, said: “Svante has not only made a huge contribution to human genetics, but also opened up an entirely new field. I am sure that all our members join with me in sending him hearty congratulations.”

An interview with Svante Pääbo can be found here: https://secure.eshg.org/interviews2015.0.html

His award lecture of 2015 can be found here: http://client.cntv.at/eshg2015/PL5Over decades, Jean-Jacques Cassiman was linked inseparably to the destiny of the European Society of Human Genetics, which he accompanied through its rebirth by facilitating the incorporation of ESHG in Belgium in 1991.

"JJ" had the role of ESHG Secretary General (1991-1997), ESHG President (2008-2009), and became first awardee of the EHSG Honorary Award in 2014. He also co-founded the International Federation of Human Genetics Societies in 1996.

Jean-Jacques passed away peacefully and serenely in the presence of his family on Friday, August 5. He will be sorely missed by all who knew and advanced together with him.

The session recordings of the ESHG Webinar on the IVD EU regulation (IDVR 2017/746) on June 22 are now available for on demand streaming.

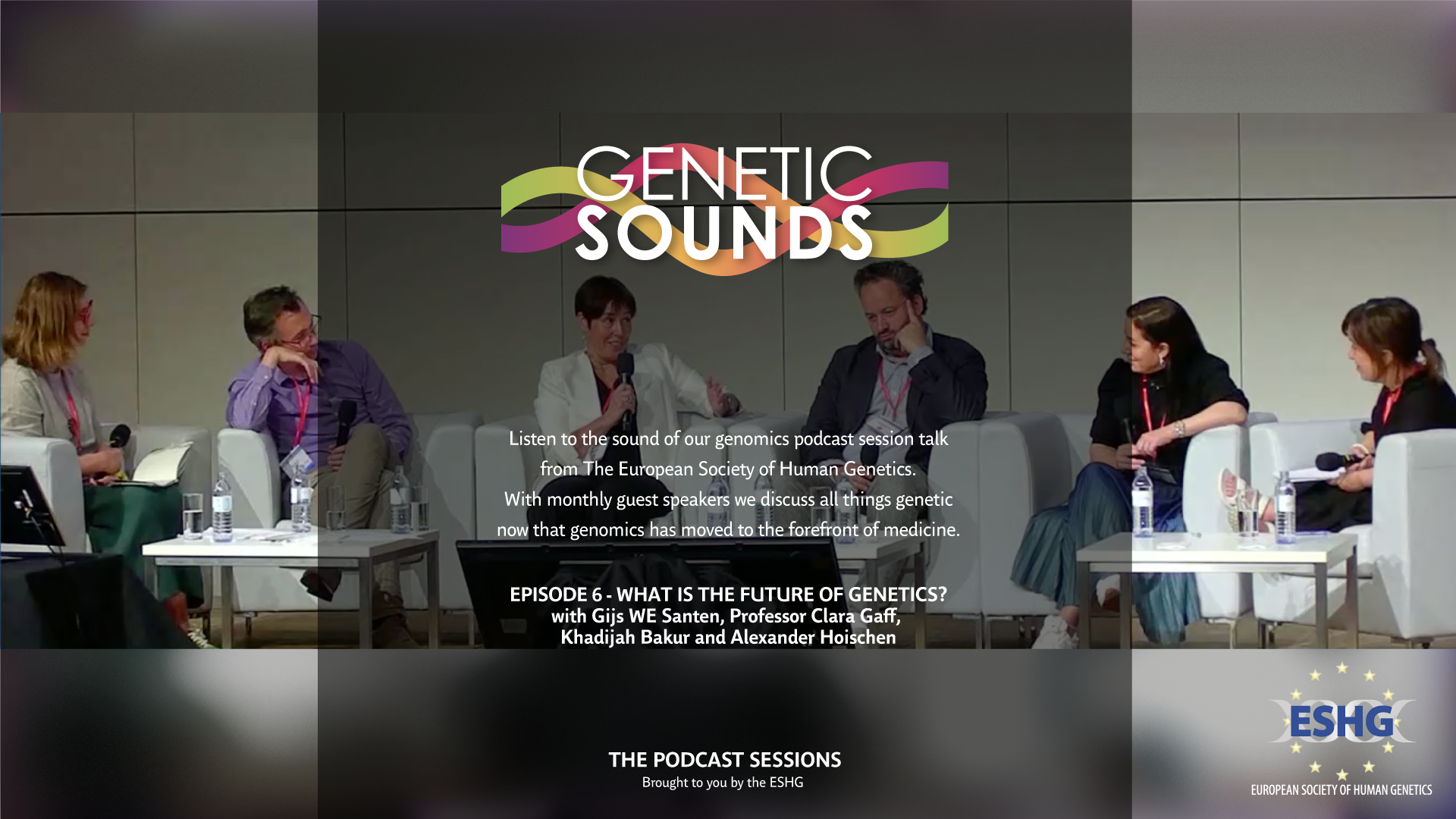

Listen to the sixth and final episode of our genomics live podcast session talk from the European Human Genetics Conference 2022 in Vienna.

In this episode, we discuss the wide topic of “What is the future in genetics?”EPISODE 6 - WHAT IS THE FUTURE IN GENETICS?

On the panel we have a wonderful range of guests including; Gijs WE Santen a clinical geneticist from the Netherlands with a special interest in dysmorphology, in particular Coffin-Siris syndrome, and prenatal genetic testing. Professor Clara Gaff, an Executive Director for Melbourne Genomics who has worked in public health, government, academic and not-for-profit sectors. Khadijah Bakur, a Genetic counsellor with expertise in understanding the role of religion -specially the role of Islam - on decision making for patients. And Alexander Hoischen, who has expertise in the identification of rare disease genes using latest genomics tools. Hosted by Nichola Garde and Mariangels Ferrer-Duch.Now available on your favourite podcast player.

The 2022 impact factor for the European Journal of Human genetics has risen to 5.31 (from 4.26), and is now ranked 35 out of 193 journals in "Genetics and Heredity".

"This reflects consistent hard work from our section editors, editorial board members and the staff of the EJHG office in Sheffield and at SpringerNature", says Alisdair McNeill, Editor in chief of the ESHG.

The winners of the 2022 ESHG DNA Day Essay and video contest have been announced. Read the best essays and watch the best videos here: www.dnaday.eu

The winner of this year’s Leena Peltonen prize, to be awarded at the ESHG annual meeting being held in Vienna, Austria, is Dr Andrea Ganna, from the Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland (FIMM), University of Helsinki and Harvard Medical School. The prize is awarded to an outstanding young researcher in the field of human genetics, and honours the memory of Dr. Leena Peltonen, a world-renowned human geneticist from Finland who died in 2010 and who contributed greatly to the identification of disease genes for human diseases.

Andrea Ganna started as a FIMM-EMBL group leader at the Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland (FIMM), University of Helsinki in 2019. He did his post-doc at the Analytical and Translation Genetic Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School and his PhD at Karolinska Institute. His research interests concern the intersection between epidemiology, genetics, and statistics, and to that end he started the FinRegistry project. FinRegistry uses nationwide registry data to build machine learning models to help better understand and predict the onset of diseases in the Finnish population.

He has authored and co-authored both methodological and applied papers focusing on leveraging large-scale epidemiological datasets to identify novel sociodemographic, metabolic, and genetic markers of common complex diseases. He currently leads two major international consortia: the COVID-19 host genetics initiative and the H2020 INTERVENE consortium. His research vision is to integrate genetic data and information from electronic health records/national health registries to enhance the early detection of common diseases and public health interventions.

Two researchers with strong ESHG connections are among the four winners of this year’s Kavli Prize for neuroscience. The Kavli Prize is given by the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters in recognition of innovative scientific research.

Jean-Louis Mandel, ESHG President from 1999-2000, is recognised for his work on Fragile X syndrome, which has led to improved diagnostic tools and become a model for other neurological diseases. The unstable repeat expansions that he discovered n Fragile X are now known as the mechanism behind more than 50 genetic disorders.

Huda Zoghbi gave the Mendel Award Lecture at the 2013 ESHG annual conference. She is honoured for her discovery, jointly with Harry Orr, another Zavli prizewinner, of ATXN1, the gene whose mutations are responsible for spinocerebellar ataxia1. She also discovered the gene MECP2, whose abnormal levels cause Rett syndrome.

The fourth 2022 prize-winner, Christopher Walsh, is honoured for his discovery of more than three dozen genes implicated in neurological disease and how they affect the development of a child’s brain.

“Understanding inherited brain disorders has been made possible by the novel genetic approaches developed by this year’s laureates,” Kristine Walhovd, chair of the Kavli Prize Neuroscience Committee, said at the award ceremony in Oslo. “Together, these four scientists uncovered the genetic basis of multiple brain disorders and in doing so, paved the way to the development of diagnostic tools and improved care for those affected.”

Dear ESHG Members,

Dear colleagues, dear friends,We wish to join other scientific societies in expressing our full support and great sympathy for the Ukrainian people, ESHG members and fellow scientists.

We greatly deplore the loss of life and destruction resulting from the invasion of Ukraine.

The ESHG being a society dedicated to academia, science, and education, we feel it is essential to support our Ukrainian colleagues and their patients at this difficult time.

The ESHG has therefore decided to grant free access to Ukrainian scientists wishing to attend our conference in June, either virtually or in person. Additionally, Ukrainian presenters of posters and talks have been granted travel fellowships.

The ESHG will also create a fund to facilitate the re-establishment of human genetics services in Ukraine as soon as the situation allows it.Should it be possible for you to employ Ukrainian genetic specialists who are able to leave the country, please consider doing so. All support is appreciated, and special dispensations are in place in many countries.

On behalf of the genetic community, we would like to encourage our members and friends to donate to charities active on the ground.

Our hearts are with all Ukrainians at this time. We all hope for a rapid end to this war.

With best regards,

Maurizio Genuardi

President of the ESHG,

on behalf of the Executive BoardPlease take a couple of minutes to take a survey on expanded carrier screening developed in cooperation with the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology ESHRE.

Your help is appreciated, whether you offer ECS at your center or not. Your input will be a very important resource for our project.

-

2021

Despite there being no evidence that polygenic risk scores1 (PRSs) can predict the likelihood of as-yet unborn children being liable to a specific disease in the future, some private fertility clinics have begun to sell PRS analyses on embryos to prospective parents. This practice raises many concerns, says the European Society of Human Genetics in a paper published today (Friday 17 December) in the European Journal of Human Genetics*.

While it is quite normal for parents to consider any genetic risks they may pass to their children, this would usually be done by performing genetic testing for chromosome anomalies or single gene related conditions. In these cases, the ability of the test to predict the development of the disease in any offspring is high.

PRSs are a completely different matter. Many conditions are caused by a complex combination of genetics and environment, and PRSs are only able to capture parts of the relevant genetic component. And when applied to selecting embryos for transfer in IVF, the PRS will relate to an individual family rather than to a wide population, and therefore will not be very useful in determining the choice of one embryo over another.

In addition, they have never undergone clinical trials to test their diagnostic effectiveness in embryos. Research on PRSs aims rather to contribute to the understanding of disease mechanisms and, perhaps more speculatively, to the management and treatment of liveborn, mostly adult, individuals. In fact, such trials in embryos would be wellnigh impossible, given that one might have to wait decades for the predicted disorder to appear (or not).

So, at present, performing a PRS test for embryo selection would be premature, at best. Adequate, unbiased information on the risks and limitations of this practice should be provided to prospective parents and the public. And it is vital that a societal debate takes place before any potential application of the technique in embryo selection. Such a debate should be focused on what would be considered acceptable with regards to the selection of individual traits, in particular. Without proper public engagement and oversight, the practice of implementing PRS tests for embryo selection could easily lead to discrimination and the stigmatisation of certain conditions.

At a time when healthcare resources are under strain, it is important that the limited money available should be spent on tests that are known to be effective. Currently, research resources would be better spent on improving knowledge about how PRSs interact with the environment in which we live, rather on the premature application to our future children of an inadequately assessed test with potentially misleading results.

*https://www.nature.com/articles/s41431-021-01000-x

1A polygenic risk score reflects an individual’s estimated genetic predisposition to a given disorder and can be used in predicting the likelihood of that individual developing the disorder

In the light of concerns about the many ethical issues posed by the handling and interpretation of DNA data from minorities, the ESHG intends to set up a (Gen)Ethics Oversight Committee (GEOC) to review and develop guidelines on ethical issues, particularly those related to population genetics. Although ESHG has no direct connection with DNA collection or the databases that are problematic in this respect, the committee will instigate a complaints procedure, as well as a route map for the handling of publications with a difficult ethical background in the Society’s journal, The European Journal of Human Genetics.

The GEOC will liaise with other ESHG committees over the development of a Society Code of Ethics, the improvement of publication practices, and the instigation of training courses on this topic. It will also investigate and make recommendations on individual cases.

“To date international scrutiny has focused mainly on unethical practices in population genetics on other continents,” said Dr Francesca Forzano, chair of the Society’s Public and Professional Policy Committee. “But there are also problems closer to home, and we need to make sure that these are dealt with effectively. DNA data used in population research must always be obtained and used in a strictly ethical way, following the rigorous standards highlighted in documents as the WMA Declaration of Helsinki. This means, for example, being certain that properly informed consent has been obtained. Sadly, we know that this has not always been the case in the past.

“Genetic research today holds out so much promise for the improvement of human health, and it is thus vital for the public good that trust should be maintained, and openness encouraged.”

The international consortium aims to tackle the major hurdle for rare disease patients – the lengthy and convoluted diagnosis journey – via an innovative research approach based on two central pillars: genetic newborn screening and artificial intelligence (AI)-based tools.

ESHG Scientific Programme Committee member Dr Serena Nik-Zainal has been awarded the UK Royal Society’s Francis Crick Medal and Lecture 2022 for ‘enormous contributions to understanding the aetiology of cancers by her analyses of mutation signatures in cancer genomes, which is now being applied to cancer therapy’. The award is made annually in any field in the biological sciences. Preference is given to genetics, molecular biology and neurobiology, the general areas in which Francis Crick worked, and to fundamental theoretical work, which was the hallmark of Crick’s science.

Professor Alexandre Reymond, vice-president of ESHG and chair of the Scientific Programme Committee (SPC) said: “I would like to congratulate Serena on a fantastic achievement. The presentation of this award underlines the chance we have to have some exceptional and dedicated scientists in the SPC, which in turn translates into the excellent science presented at our annual conference.”

The ESHG is happy to announce that more than 4,000 delegates from 84 countries participated in the second virtual European Human Genetics Conference from August 28-31, 2021.

The ESHG wishes to thank all scientific attendees and especially our industry partners for their continuous support through those challenging times.

Missed a presentation? No problem, all talks, posters and session "re-lives" are still available until November 1.

Missed the entire conference? Also no problem, you can still register at discounted fees to watch all presentations on demand until November 1.

Prof. Thierry Frébourg passed away on the 13th of March at the age of 60 years. An active member of ESHG, he has worked in the Scientific Program Committee and for several years as Section Editor of the European Journal of Human Genetics.

He was the founder of the clinical genetic services of Normandy and of a mixed University-Inserm research unit in Rouen. His clinical and scientific achievements and organization skills were appreciated nationwide, and he was assigned important roles in national scientific organizations.

One of his major scientific interests was in the TP53 related tumor predisposition syndrome. He had the goal to improve the treatment of patients affected with these tumors and cancer prevention in carriers at risk, and has closely collaborated with the French Li-Fraumeni Syndrome Association and with the European Reference Network on genetic tumour risk syndromes (GENTURIS). His last achievemnt in the field has been the publication of clinical guidelines, an essential step towards the standardization of care for subjects dealing with this rare condition.

The French and the European human genetics communities will greatly miss him, along with his enthusiasm for science and dedication to patients.

The compulsory collection of DNA being undertaken in some parts of the world is not just unethical, but risks affecting people’s willingness to donate biological samples and thus contribute to the advancement of medical knowledge and the development of new treatments, says a paper in the European Journal of Human Genetics, published online* today [18 January 2021].

Citing abuses being carried out in China, Thailand, and on the US/Mexico border, the authors1 call on scientific journals to reexamine all published papers based on databases that do not meet accepted standards of ethical approval, and demand an end to collaborations between academic institutions worldwide and those in countries carrying out unethical DNA collections. They also advocate that companies making equipment used in DNA analysis should stop sales to the institutions involved in ethically tainted genetic research.

While journals ask that studies submitted to them should have ethical approval, they may fail to recognise that some ethics committees do not abide by expected ethical standards. Citing the compulsory collection of DNA samples from ordinary people being carried out by the Chinese authorities in Xinjiang province as part of a programme of surveillance and control, the authors say: "It appears that almost half of over a thousand articles describing forensic genetics studies in Chinese populations have at least one co-author from the Chinese police, judiciary, or related institutions. It is impossible to carry out forensic population genetics research in China independently from the Chinese authorities. All this literature is thus potentially ethically tainted."

The paper calls on publishers to conduct a mass reassessment of the literature and to require further information on consent and ethical approvals, in addition to considering whether the studies fulfill the basic ethical requirements for non-maleficence, beneficence, justice, and veracity. "Such an assessment would be important if, in the future, any doubt arises about the data and the uses to which they may be put."

Companies should reconsider their position too, says the paper. Thermo Fisher Scientific has decided to stop sales of equipment to Xinjiang police forces, but such action by one company alone is insufficient to tackle the problem. "The only effective way would seem to be to stop sales to police and judiciary forces across China of products used in the identification of humans by means of molecular genetics. Other Western suppliers, such as Promega and QIAGEN, should follow suit."

The example of Kuwait is encouraging, say the authors. In 2015, the Kuwaiti government became the first in the world to introduce a law requiring the compulsory collection of DNA samples from all citizens, residents, and visitors to the country. Such a measure was introduced purportedly to discourage terrorism, but many suspected that it could lead to genetic discrimination against some vulnerable minorities. The following year, after an international campaign against the measure, the law was dropped.

"While China, the USA, and Thailand are very different countries from Kuwait, both in their size and their leadership, the Kuwaiti example gives us reason to hope that international pressure may have an effect. We are concerned that the growing public awareness of abusive DNA collections will have a detrimental effect on the image of genetics in the wider world," say the authors.

"In this time of COVID-19, Chinese science is increasingly under scrutiny from all quarters. The country’s reaction to the pandemic has been widely praised. It is surely not in their interest to damage their standing in the scientific world by continuing with what are clearly unethical and discriminatory practices," they conclude.

(ends)

*https://www.nature.com/articles/s41431-020-00786-6

1 Dr Francesca Forzano, Prof Maurizio Genuardi, Prof Yves Moreau, writing on behalf of the European Society of Human Genetics

-

2020

There has been considerable discussion of Covid-19 vaccination on social media, and some posts have led people to be concerned that the new messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines will change their DNA. In an attempt to clarify the situation, the European Society of Human Genetics would like to reassure the public that there is no evidence to support such concerns and that, if there were, we would not hide it.

mRNA vaccines do not change DNA. Rather, they introduce molecules that lead to the production of harmless small fragments of the virus into cells. This causes the cells to make a part of the virus protein that strongly activates the immune system to produce a response against it. In this way the body will respond quickly when it comes into contact with the real, whole virus.

Vaccination prevents serious forms of Covid-19, including its potential complications. Individual genetic makeup (DNA) remains unchanged. All that happens is that the production of antibodies and defensive white blood cells is stimulated, in exactly the same way as happens when someone gets a viral infection naturally. The mRNA in cells is broken down very quickly and cannot reproduce itself. Thus the mRNA fragment cannot merge or directly integrate with the individual’s own natural DNA.

In a letter published in The Lancet, a group of British experts have warned that a no deal Brexit could result in the exclusion of the UK from the 24 European Reference Networks (ERNs) that work to improve the care of patients with rare diseases. ERNs were set up because no one country has the expertise or resources to cover the thousands of rare diseases, and geneticists are particularly involved in the diagnosis and treatment of rare disease patients, and as such, with ERNs. « We would be saddened if, as a result of Brexit, the UK were to be excluded from ERNs in the future, and we believe this would be very harmful to British patients living with rare diseases. We hope sincerely that an acceptable solution may be found before the end of the year, when the change will come into effect, » said ESHG President-elect Professor Maurizio Genuardi.

“GertJan was the heart of the EJHG. We will remember his enthusiasm, his argumentation, and all he did for the Society in general. We thank him.” said ESHG President Alexandre Reymond, opening the Board meeting that took place on Friday 13 November.

This sentiment will be echoed by all who knew and worked with GertJan, who was editor in chief of the European Journal of Human Genetics for the last 25 years, as well as being president of the ESHG in 2002-2003, and the ESHG Award Laureate in 2011. In the interview he gave for the latter, he summed up his approach to science – and to life. “I like to do repairs; to look at things, find out what’s broken, and then do something about it.”

GertJan undertook his studies in Amsterdam, where he lived until his death. He was head of the Human Genetics department at Leiden University Medical Centre from 1992 to 2012. His main scientific interest was in neurodegenerative and neuromuscular disorders such as Huntington’s disease and Duchenne muscular dystrophy. He made major contributions to the treatment of both, for example discovering a therapy that induced exon skipping in DMD. He was one of the first to see this potential use of exon skipping: “We can use it for interfering in biological processes like moving proteins around and blocking signals. The interesting thing about antisense RNA relative to RNAi is that you can tweak its activity more precisely, rather than just destroying it, and thereby regulate many different processes.”

He will be remembered for his scientific prowess, but it is perhaps his humanity and wit that will linger longest in the hearts of those who knew him. He was an inspiring mentor to many young scientists and enjoyed setting up collaborations. “So many people have complementary skills, but sometimes in national science policy they are too busy making people compete and forget how much more you can achieve jointly with a large group of people, especially in the science of today. I enjoy trying to get these groups of people to work together.”

He admitted that he only half-seriously suggested that he might become editor of the EJHG following Giovanni Romeo (“I had been a pop music critic and then editor of a computer journal”), and said that he was honoured, but also scared, when offered the job. And what a job he made of it! The EJHG went from a bimonthly journal of a few hundred pages to a monthly with nearly 2000, and the impact factor rose steadily.

GertJan was tireless in the pursuit of excellence in every area of his life; a wonderful colleague and collaborator who will be missed by so many people. ESHG sends our deepest condolences to his family, of whom he spoke with so much affection.

A European geneticist is one of the two winners of this year’s Nobel Prize for chemistry, the first time that two women have shared the prize. Emmanuelle Charpentier, from the Max Planck Unit for the Science of Pathogens, Berlin, Germany, and Jennifer A Doudna, from the University of California, Berkeley, USA won the prize for the invention of CRISPR/Cas9, or "the development of a method for gene editing", according to the citation from the Nobel committee.

"Professor Charpentier gave a most exciting and interesting talk as the Society’s Mendel Lecturer in 2018. In the eight years since its discovery, CRISPR/Cas9 has made remarkable contributions to basic and applied research, and has taken life sciences into a new era," said ESHG President Professor Alexandre Reymond. "We send our heartiest congratulations to the winners."

You can read an interview with Professor Charpentier here.

ESHG strongly recommends that Article 5-§5 conditions (d) to (i) for in-house exemptions are removed from the IVD Regulation, while conditions (a) to (c) are kept. Failure to do so will increase health care costs and jeopardize our ability to design precise “personalized” laboratory tests (necessary for precision medicine) and to adapt to shifting test needs (like repurposing instruments for covid-19 testing).

The New York Times reported on 17 June 2020 that the Chinese government is collecting DNA from ordinary people as part of a programme of surveillance and control. This is in contradiction to existing regulations and safeguards concerning the collection of DNA samples from individuals. Collection of DNA without the subject’s full, informed consent can only be justified in limited circumstances, for example to solve a serious crime. A collection of samples from individuals where no such consent has been given, or where it has been obtained by extortion, has been ruled illegal by many international bodies, and the very existence of such a database is dangerous.

ESHG calls on responsible authorities worldwide to ensure that human DNA is collected only from individuals suspected of having committed serious crimes. Obtaining and documenting informed consent is an essential cornerstone of the proper research, clinical, and/or diagnostic use of DNA samples. We are of the opinion that existing databases that do not abide to established legal and ethical principles should be destroyed, and that companies should not provide technology to be used for these purposes, until there is clear evidence that human rights are no longer being violated.

A number of ESHG members have been the target of a scam scheme (a variation of the “CEO scam” adapted to associations https://cba.ca/how-to-spot-ceo-scam), which has been around in a number of scientific associations in recent months. The scammers research the websites of associations, impersonate the president, or one of the board members (often very convincingly) and contact other fellow colleagues to make a money transfer to their account.

They try to create a situation, which sounds plausible without giving too many details (which would uncover them), but still enough so that members may actually believe it is genuine. Often they will uncover their plan only in the second or third email after they engaged a member in an email conversation. Unfortunately experience has shown that this can become an actual threat.

Be very careful, when you receive such an email. Please always check the actual address that will be displayed when you click on „reply“. These people are technically proficient, so they may make appear the name of a friend or their email address in the email you receive (this is called „spoofing“), but when clicking on reply you will see the real address of the sender/scammer (which is different from the one you know).

Please do not actually reply to this person! And do not cc other people as you are giving away their email addresses and make them the next possible target. Note that this is not necessarily an indication that your colleague’s mailbox was hacked, but rather that scammers are impersonating a person you supposedly know.

Use caution when forwarding the email to your colleague to make them aware. Make sure to "forward" and use the real address you have on file (do not hit “reply”), as obviously the scammer will confirm that he is the "real deal".

They are unfortunately rather convincing and successful. So please be aware that you may also become the next target.

-

2019

An ad hoc working group in ESHG (Johan den Dunnen, Helen Firth, Nicole de Leeuw, Hans Scheffer and Gunnar Houge) has proposed a two dimensional system for variant classification, with a molecular and clinical arm. Everybody is free to test the system, and feedback is highly appreciated! The system with information and explanations use can be found here.

The past year has seen many developments in the field of gene editing, both in somatic and in germ line applications. Editing the germline means that changes will be made in every cell in the body and will be inherited by future generations. While carrying out such editing in a research setting is important for a greater understanding, clinical germline editing leading to a pregnancy carries considerable practical and ethical risks, at least at present.

The announcement of the birth of twins in China, following a procedure of germline gene editing performed by Dr He Jiankui, has attracted the attention of the international media, as well as raising serious concerns in the scientific community, and the Chinese authorities also condemned these procedures as being illegal in the country. A few scientists in the USA were informed about the intentions of Dr He Jiankui both before and during the course of his experiments. However, formal reports to ethics committees or other relevant institutions were never made.

Now clinical germline gene editing has taken place, and the scientific community worldwide has been shaken and is questioning its responsibilities.

Over the past years, there has been a general consensus that it would be irresponsible to carry out any clinical germline gene editing at the present time, and that there is a need to promote research to build up a robust core of knowledge on the subject, as well as to explore more broadly the views of society on the scope and limits of this research and its potential future application. ESHG has contributed to these discussions and to this general consensus, notably through our Recommendations on Germline Gene Editing released in April 2018, and jointly signed with ESHRE.

Notwithstanding the wide scientific consensus on the inadvisability of clinical germline gene editing, clinical experiments have taken place. For this reason, a group of eminent scientists (Lander et al) has proposed that the scientific community should take a stronger position in the form of a moratorium on clinical, heritable, gene editing.

The moratorium would not prevent human germline gene editing research that will not lead to a pregnancy, neither will it discard the possibility of introducing germline gene editing in the future should nations so wish after adequate and thorough reflection, together with appropriate and sound international dialogue and supervision.

Such a moratorium will mean that every scientist pledges to adhere to a moral code of conduct according to which they will voluntarily refrain from and will not support any use of clinical germline editing - unless certain, clearly-defined conditions are met. These latter would entail a period of public notice of the specific intents, during which there would be robust international discussion about the pros and cons of doing so. Within individual nations there would also be debate to explore whether a broad societal consensus on whether to proceed with clinical human germline editing at all might be reached, as well as on the appropriateness of the proposed application.

The moratorium will also entail potential collaborators, ethics committees and peer-reviewed journals observing a ‘scientific embargo’. Such journals are the gatekeepers of trustworthy scientific communication across the world, and this requirement will involve more stringent ethical review and filtering.

As a scientific society with a commitment to contributing to the responsible translation of advancements in human genetics into a benefit for patients and society as a whole, we believe that it is our responsibility to make an unequivocal statement on this issue in response to the plea of our eminent colleagues, in order to provide clear direction to our members.

The ESHG, while considering fundamental and pre-clinical safety research on human germline editing to be not only justified, but necessary, supports the call for a global moratorium on all clinical uses of human germline editing - in sperm, eggs or embryos - that will lead to a pregnancy and/or to the creation of genetically modified children.

We urge relevant institutions to consider this plea for a moratorium in all their pertinent rulings, and to provide appropriate information to society as a whole so that adequately informed discussion may take place.

Two years ago, ESHG condemned the collection of DNA from ordinary individuals in China as part of an oppressive programme of surveillance and control of the Muslim Uyghur population in Xinjiang. Since then, both the size and the evidence of the misuse of this database have been growing. The around 10 million Uyghurs are already suffering state repression. All passport applicants are now required to provide DNA samples, irrespective of whether or not they are suspects in a criminal case. This is in total contradiction to all existing regulations and safeguards concerning the collection of DNA samples from individuals.

DNA technology is in itself neutral and has legitimate and beneficial applications in many areas of healthcare when used ethically with informed consent, and in forensics when used in an appropriate legal framework. But collection of DNA without the subject’s full, informed consent can only be justified in extremely limited circumstances, for example in order to solve a very serious crime. A collection of samples from individuals where no such consent has been given, or where it has been obtained by extortion, has been ruled illegal by many international bodies, and the very existence of such a database is dangerous.

Once more, ESHG calls on the Chinese government to follow in the footsteps of all responsible authorities and ensure that human DNA is collected only from individuals suspected of having committed serious crimes; obtaining and documenting informed consent is an essential cornerstone of the proper research use of DNA samples. We applaud the reported action of the ThermoFisher company in refusing to supply its equipment to Xinjiang, and also call on other companies providing the technology used in this collection to halt sales to Chinese police forces until the issue has been resolved satisfactorily, i.e. that human rights are no longer being violated in this way.

-

2018

The ESHG joins the American Society of Human Genetics in denouncing the misuse of genetics in support of racial theories. Not only is this dangerous and immoral, but it also has no base in science. Although it is possible to claim that a person belongs to a particular race based on their appearance, race cannot be identified by genetics.

Our members are dedicated to improving human health and well-being, for all, and we condemn very strongly any attempt to use our work to the benefit of any particular section of society, or to propagate hate and extremism.

A number of talks from previous conferences are available as on demand web-cast via ESHG's YouTube Channel.

In recent months, there have been reports in the media concerning the use for law enforcement purposes of personal genetic information submitted to commercial companies in the interests of determining ancestry. This has raised questions that need wider scrutiny and debate.

Such ancestry databases collect and store genetic information provided by paying customers who, in exchange, obtain access to a database where they may be able to find genetic matches with other customers, and so establish a degree of relatedness. Companies usually state that consumers’ genetic information will be kept private and confidential within the context of the ancestry database and will not be shared with third parties without their consent, with the exception of their being compelled to do so by law enforcement authorities.

A clear definition of the categories or limits of such cases is not provided by the companies, since this would be variable depending on the circumstance, as well as from country to country. However, this unavoidable imprecision may leave room for misinterpretation and an incomplete understanding of the facts from the customer’s perspective.

The legal framework under which any one company selling ancestry testing and holding the database operates is another potential problem. It would be plausible to assume this would be according to the regulations of the country where the company is registered, which might in itself not be familiar to the customer. However, it would be reasonable to speculate that there might also be a complex interplay with the legal framework of the country of origin of the customer, as well as of international regulation, particularly when serious crimes or immigration policies are involved.

Furthermore, the customer might reasonably assume that such particular circumstances would apply in the case where they themselves are suspected of committing a crime. Instead, those cases reported recently show that access to these databases has been exploited by authorities for the purpose of looking for relatives or fellow nationals of a suspect, who is not himself a customer of the company, with the aim of confirming identity or nationality. In order to do this, every search has to examine data from a large group of customers and not only one individual or a small, restricted group. This represents a serious threat to the privacy of individuals not suspected of committing a crime.

This is not an ‘in principle’ matter. Instances of non-paternity, for example, could be revealed through this process. If others were to gain access to the database, this information could be exploited for personal or even criminal reasons.

Informed consent of the person involved is waived in cases of law enforcement, but such consent is still needed for the initial request for testing and registration to the database. Understanding this level of complexity is not trivial and can test the implication of ‘meaningful’ alongside ‘informed consent’.

Finally, the use of commercial databases containing data acquired mainly for ‘recreational’ use, might not be fully compliant with the recently published guidelines for the storage and use of genetic data (Forensic Genetics Policy Initiative’s 2017 Report: ‘Establishing best practice for forensic DNA databases’) from a technical and procedural perspective.

On this basis, we would encourage all relevant stakeholders to start discussions on the use for forensic purposes of genetic information available in the public domain and in non-forensic databases. Access to a private genetic information outside of the scope of the individual consent is an exception that responds to a specific goal: to contribute to justice. This access must be established through laws or the constitution, so as to guarantee the protection of innocent people.

We urge current and future customers to acquire all the information needed before undertaking commercial genetic testing, particularly for purposes that are not health-related.

The Council of Europe’s protocol on genetic testing for health purposes* came into force yesterday (Sunday 1 July). The protocol, an addition to the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, lays down rules on the conduct of genetic tests, including direct-to-consumer testing. It specifies the conditions under which tests may be carried out on persons not able to consent, with particular attention to children, and addresses privacy issues and the right to information obtained through genetic testing. It also covers counselling and screening.

The protocol enters into force thanks to its ratification by five Council of Europe member states (Norway, Montenegro, the Republic of Moldova, Slovenia and Portugal). It has also been signed by five others – the Czech Republic, Finland, France, Iceland and Luxembourg. The major push for ratification came from the Czech Presidency of the Council of Europe, following extensive lobbying by the Czech Society of Medical Genetics and Genomics. “It was a major effort on our part,” says Professor Milan Macek, President of the Czech Society, “and we are delighted by the result.”

“At a time when genetics and genomics are advancing so rapidly, issues surrounding genetic testing take on an even greater importance than before,” says ESHG President Professor Gunnar Houge, University of Bergen, Norway. “New technologies and discoveries provide huge potential for the improvement of human health, but alongside that can go the potential for misuse. The ESHG therefore welcomes the Council of Europe protocol and believes that it will be an important factor in ensuring that genetic progress continues to be applied in the most ethical way possible to the benefit of all concerned.”

*https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2986683/pdf/ejhg200984a.pdf).

Many parts of the ESHG website have been re-grouped in a more comprehensive manner, e.g. the Public and Professional Policy information as well as the Genetic Education part.

We would like to draw special attention to the Educational Resources, which have been excellently put together by Education Commtitee member Edward Tobias.

The website is now also mobile responsive and will provide a much better experience on your mobile device.

We would be interested to know, if you have recently been thoroughly impressed by one or more speakers you have seen at a meeting (obviously outside the ESHG Annual meeting), both in terms of being an excellent speaker and of presenting excellent science.

We look very much forward to receiving your input at your earliest convenience, in order to discuss it at the next SPC meeting end of June, but we will keep the online form open over the whole year and are equally happy to receive a feedback whenever you experienced a great talk at a meeting.

Thank you very much!

It is with sadness that that I heard the announcement of the death of John Sulston this week. Other commentators have remarked on his contribution to the first working draft of the human genome and the clarity with which he argued that this science should be in the public domain.

I had the privilege of beng his colleague on the UK Human Genetics commission. I remember not only his intellect and humanity but also that he was great fun. My time on this Commission was one of the most formative in my professional life and much of that was due to working with colleagues such as John. My sympathies go to his family, friends and colleagues.His contribution to the science of human genetics should be acknowledged and his personal qualities remembered.

Christine Patch

President of the ESHG -

2017

The repeal of the law mandating the collection of DNA from all Kuwaiti residents and visitors to the country is good for individuals concerned about their privacy and human rights, and for medical and scientific research in Kuwait and worldwide. The law as proposed would have been ineffectual in its stated purpose – fighting terrorism – and the simple existence of such a database could have been dangerous in the future, for example in the case of hacking or régime change. It could also have dissuaded people from voluntarily donating DNA for research purposes because of uncertainty as to the real purpose of such a collection, with serious consequences for progress in human genetics.

If the law had been brought into force, Kuwait would have been the first country in the world to require the compulsory collection of human DNA samples from all citizens. The Forensic Genetics Policy Initiative report, ‘Establishing Best Practices for Forensic DNA Databases’, published last week, says: "As countries develop legislation to govern DNA databases, it is important that civil society is engaged in the debate about what safeguards are needed to protect human rights."

We congratulate the Emir of Kuwait and the Constitutional Court on their willingness to listen to those expressing concerns about this, and hope that other countries that may be considering going down the same road will take note of this decision.

For immediate release: Thursday 16 March 2017

A Bill that would allow companies to require employees to undergo genetic testing and disclose the results to their employers, or risk having to make health insurance payments of thousands of dollars extra, was recently approved by the US House of Representatives Committee on Education and the Workforce, with all 22 Republicans supporting it and all 17 Democrats opposing.

Genetic tests can predict health risks. In the US, where companies cover significant parts of the health insurance of their employees they may, understandably, want to minimise these risks. In the past, however, decisions on whether or not to undergo genetic testing have been the voluntary choices of individuals. Both the Council of Europe and the US law (Genetic Information and Non-Discrimination Act, GINA) uphold this standpoint.

The European Society of Human Genetics (ESHG) defends the principle that employees should be employed on the basis of their skills and expertise, and not on their future health risks. This Bill has apparently been integrated into the activities related to the revision of the Affordable Care Act, otherwise known as Obama Care. Transparency is needed on the potential decision to discontinue the GINA. The genetic and health information of individuals needs protection,” said Professor Martina Cornel, chair of the ESHG Public and Professional Policy Committee.